Suppose that you were a historian and you were seeking to

use written sources to investigate an event from the distant past. What

standards would you use to identify reliable sources? Likely you would want the

sources to be written by someone who had actually witnessed the event, or at

least someone who was closely associated with eyewitnesses and had carefully

investigated the matter. It would be best if the sources were written close to

the time of the actual events, within the lives of surviving eyewitnesses. A

large number of manuscripts would help to verify the contents of the original

documents and the earlier the manuscripts were copied, the better. Finally, it

would be ideal if other written documents and archeological discoveries

corroborated some of the information within the sources.

Well, if your criteria would resemble those listed above,

then you have just described the New Testament. Viewed in light of these criteria,

the New Testament is far and away the most reliable source by which to

investigate ancient history. Yet, the New Testament is often dismissed as

unreliable because it is “biased” and contains accounts of the miraculous. We

will address those claims at the end of this post. However, first we will put

the New Testament through the tests that are suggested above to see how it

stands up as a historical source. I feel it important to do this upfront

because sometimes skeptics dismiss data in the case for the resurrection simply

because it comes from New Testament documents.

One misconception

is that the New Testament is a single source, but, in reality, it consists of

over twenty different documents representing a variety of genres. These include

the four gospels that describe the life of Jesus, a history of the early

church, numerous letters from church leaders to entire churches or specific

individuals, and a prophetic vision of the end times. When examining the case

for the resurrection, key data obviously comes from the four gospels, but also

from Acts (the history of the early church) and from several of the letters or

epistles. To determine the reliability of these documents as historical

sources, there are two questions that must be answered: Have the contents of

the original documents been preserved and, if they have, can we trust those

contents?

Have the contents

of the New Testament documents been reliably conserved?

A popular cliche

on the internet is that the New Testament documents, and the gospels in

particular, are like a game of telephone. Surely, you have played the game?

This is how New Testament scholar and skeptic Bart Ehrman describes it:

“You are probably

familiar with the old birthday party game “telephone.” A group of kids sits in

a circle, the first tells a brief story to the one sitting next to her, who

tells it to the next, and to the next, and so on, until it comes back full

circle to the one who started it. Invariably, the story has changed so much in

the process of retelling that everyone gets a good laugh. Imagine this same

activity taking place, not in a solitary living room with ten kids on one

afternoon, but over the expanse of the Roman Empire (some 2,500 miles across),

with thousands of participants—from different backgrounds, with different

concerns, and in different contexts—some of whom have to translate the stories

into different languages.”1

To Ehrman, the

problem is grave. He also writes:

“Not only do we

not have the originals [of the New Testament documents], we don’t have the

first copies of the originals, we don’t even have the copies of the copies of

the originals, or copies of the copies of the copies of the originals. What we

have are copies made later—much later.... And these copies all differ from one

another, in many thousands of places.... These copies differ from one another

in so many places that we don’t even know how many differences there are.”2

While these

statements are rhetorically powerful, they distort the reality of the high

degree to which the New Testament has been reliably transmitted from the

original writings to the present day. Two things that Ehrman says are true.

First, it is true that we do not have the original New Testament documents and

that most early manuscripts were copied over one hundred years after they were

first penned. Second, there are thousands of variants or differences between

the manuscripts that we do have. In fact, there are more variants than there

are words in the New Testament.

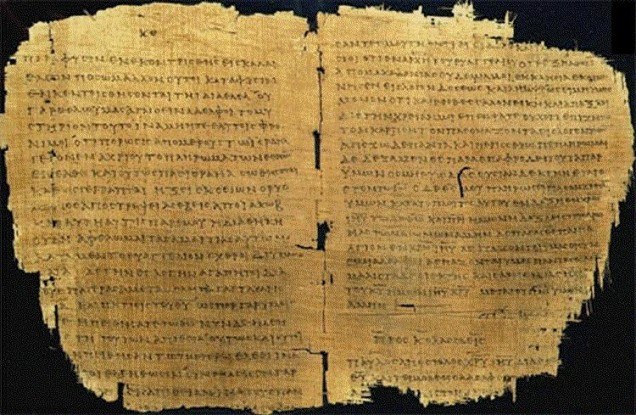

Fortunately,

neither of these are a problem because of the incredibly large number of New

Testament manuscripts that have been preserved or discovered, which far

outpaces other ancient documents. While these numbers change as new discoveries

are made, as of 2014, a total of 5,838 Greek New Testament manuscripts and

18,524 non-Greek New Testament manuscripts had been discovered. The earliest

fragment of a manuscript is a portion of the gospel of John which dates to

about 130 A.D., about 50 years after the gospel was written.

Let’s compare that

to other ancient documents. Homer’s Illiad is by far the next closest

competitor with over 1,800 manuscripts, but the earliest manuscript was written

over four hundred years after the original. The next closest, Demosthenes’ Speeches,

drops to only 340 manuscripts with the earliest written over 1,000 years

after the original.3 To help visualize the difference, textual critic Dan

Wallace provides the following picture:

“The wealth of

material that is available for determining the wording of the original New

Testament is staggering: more than fifty-seven hundred Greek New Testament

manuscripts, as many as twenty thousand versions, and more than one million

quotations by patristic writers. In comparison with the average ancient Greek

author, the New Testament copies are well over a thousand times more plentiful.

If the average-sized manuscript were two and one-half inches thick, all the

copies of the works of an average Greek author would stack up four feet high,

while the copies of the New Testament would stack up to over a mile high! This

is indeed an embarrassment of riches.”4

This incredibly

large number of manuscripts allows textual critics to reconstruct what was

written in the original New Testament documents. While there are many variants

or differences in the manuscripts, most of which are spelling errors, comparing

different manuscripts allows scholars to work back to the original words of the

authors. This leads Bart Ehrman, the same guy who compared the New Testament to

a game of telephone, to write:

“Besides textual

evidence derived from New Testament Greek manuscripts and from early versions,

the textual critic has available the numerous scriptural quotations included in

the commentaries, sermons, and other treatises written by the early Church

fathers. Indeed, so extensive are these citations that if all other sources for

our knowledge of the text of the New Testament were destroyed, they would be

sufficient alone for the reconstruction of practically the entire New

Testament.”5

So the answer to

the first question is a resounding, “Yes!” The New Testament is the most

reliably preserved document from ancient history. If a person claims that the

New Testament has not been reliably transmitted through time, then, if

consistent, they would need to reject every other document from ancient history

as even more unreliable.

Can we trust the

contents of the New Testament documents?

Since we can

confidently conclude that the words of the New Testament have been reliably

transmitted across almost 2000 years, the next obvious question is whether we

can trust what was originally written. To analyze this question, we will return

to the criteria that were suggested at the beginning of this post.

It is essential that the authors of the gospels and other

New Testament documents that refer to the resurrection either witnessed the event

directly or were close associates of those who had. The gospels were originally

written anonymously, but that was standard practice for Greco-Roman

biographies, the literary genre under which the gospels are most likely

classified. Writings of early church fathers identify Matthew, Mark, Luke, and

John as the authors. Matthew and John were Jesus’ disciples and would have been

direct eye-witnesses of most of the material in their accounts. Mark was

mentored by Peter, another disciple, and Luke was an associate of the Apostle

Paul and had access to other disciples, as well. It should be noted that some

scholars dispute the authorship of the gospels, but strong cases can be made

for the traditional attributions. It is beyond the scope of this post to make

those cases here, but if you are interested, the following article defends the position that Peter provided eye-witness source material for

Mark’s gospel.

Related to the topic of authorship, it is also

important that New Testament documents were written within the lifetime of

eyewitnesses of the resurrection. This is important for a number of reasons.

First, it means that the authors could either be direct eyewitnesses or have

access to eye-witnesses of the events reported in the gospels and epistles.

Second, it means that other eye-witnesses were still alive to either confirm or

deny these reports. Finally, it puts to rest any conspiracy theory that the

gospels were written by some mysterious figure in a dark room during the 3rd

century.

Conservative estimates have the gospels written

sometime between 60 – 90 A.D., but a strong case can be made for dating most of

the gospels either prior to or at the front of this window.

Let’s start with the gospel of Luke, who also

subsequently wrote the book of Acts recording the early history of the church.

If Acts was written after 70 A.D., then Luke, who was a historian that

“carefully investigated everything from the beginning,” (Luke 1:1-3) curiously

left out an enormous event in the history of the church. That is the year that

the Roman army destroyed the city and temple of Jerusalem. Imagine reading a

history of New York City that did not include an account of the attack on the

Twin Towers. You would automatically know that the history had been written

before September 11, 2001. In the same way, a history of the early church that

omitted the destruction of Jerusalem must have been written before 70 A.D.

Furthermore, Acts also fails to report the martyrdoms

of Peter (65 A.D.), Paul (64 A.D.), and James the brother of Jesus (62 A.D.).

In fact, when the book of Acts ends, Paul is still under house arrest in Rome.

This evidence strongly suggests that Acts was written sometime in the early

60’s, before these events occurred. Therefore, the gospel of Luke, which he

refers to in Acts as “his former book” (Acts 1:1), must have been written

before this date.

Yet, there is more. The general consensus among

scholars is that 1 Corinthians was written in 56 or 57 A.D. In his letter to

the Corinthian church, the Apostle Paul quotes Luke’s version of the last

supper, the only version that uses the words “do this in remembrance of me”

(compare 1 Corinthians 11:23-25 and Luke 22:19-20). In that case, Luke’s gospel

would need to be written before 56 A.D.

Finally, Luke appears to extensively quote portions of

Mark and Matthew in his gospel. Luke admits that he is not an eye-witness of

the events, but has carefully collected statements from those who were present.

In that case, Mark and Matthew would need to have been written in either the late

40’s or early 50’s in order for Luke to draw from them.

This puts at least three of the gospels written within

about twenty years of the resurrection. That might seem like a long time, but

consider that the earliest surviving sources describing the life of Alexander

the Great were written about 300 years after his death. In terms of ancient

history, twenty years is practically right on the event and far too little time

for legend to develop. However, the gospels are not the only New Testament

documents that describe the resurrection.

In 1 Corinthians 15:3-7, the Apostle Paul quotes what

is believed to be a creed of the very early church.

For what I received I passed

on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to

the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day

according to the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, and then to the

Twelve. After that, he appeared to more than five hundred of the brothers and

sisters at the same time, most of whom are still living, though some have

fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles...

Even skeptical scholars concede that this creed most

likely developed less than three years after Jesus death and reported

resurrection.6 That is practically breaking news of the event

itself. What all this means is that the New Testament data on the resurrection

is coming from people who were in a position to witness the events themselves

or carefully interview eyewitnesses and we can trust that they were able to

serve as reliable sources of the resurrection.

Yet, the question remains, were they reliable sources?

They may have been in a position to accurately and truthfully report on events

in question, but they also could have created the resurrection story.

Fortunately, there is strong internal evidence within the gospels that supports

the truthfulness of their testimony.

First, the criterion of embarrassment is a type of

critical analysis in which an account that is embarrassing to the author is

considered more likely to be true, because the author would have most likely

not include such humiliations in a fabricated tale. The gospels include several

such details about the disciples, two of which authored gospels and others that

provided source testimony, that meet the criterion of embarrassment. The

disciples fail to trust Jesus while sailing during a storm (Mattew 8:23-27,

Mark 4:35-41, Luke 8:22-25); Jesus rebukes Peter with the strong terms, “Get

behind me, Satan!” (Matthew 16:23, Mark 8:33); the disciples rebuke children

for coming to Jesus (Matthew 9:13-15, Mark 10:14, Luke 18:15; the disciples

fall asleep while praying with Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane (Matthew

26:36-46, Mark 14:32-42), the disciples repeatedly don’t understand Jesus’

teachings and parables (Matthew 15:16, Mark 7:17-18, Luke 18:34, John 13:28);

all of the disciples run away when Jesus is arrested (Matthew 26:56, Mark

14:50); and Peter denies Jesus three times (Matthew 26:69-75, Mark Mark

14:66-72, Luke 22:54-62, John 18:15-18,25-27).

Yet, probably the most significant embarrassing detail is

that women were the first eyewitnesses of Jesus’ resurrection (Matthew 28:1-10,

Mark 16:1-8, Luke 24:1-10, John 20:1-18). From our cultural perspective, it

probably seems offensive to say that this is an embarrassing detail. However,

in first-century Palestine, a woman’s testimony was not considered to be

credible, a fact confirmed by both the Jewish historian Josephus and the

Talmud.7 If the gospel writers concocted the whole resurrection

story, there is no way that they would make women the first people to see the

risen Jesus, when this detail would make the resurrection claim less

trustworthy. The only logical explanation for the inclusion of this important

detail is that it is actually true.

Second, the gospels contain several unintentional

coincidences, which serve to corroborate each account. When witnesses of a

crime give exactly identical testimonies, a detective will likely be concerned

that the witnesses have conspired to line-up their accounts. What is preferred

is to have slightly different accounts, with the same core message, that support

and corroborate each other. Consider just one example from Lydia McGrew, author

of Hidden in Plain View, a book that explains how unintentional coincidences strengthen the

reliability of the New Testament.

In John 13 we're told that

Jesus got up after eating the Last Supper and washed the disciples' feet. It

just sort of happens out of the blue. Reading only John, you might think that

Jesus thought of this idea for no special reason, and it does raise the question,

"Why did he do that just then?" If you go over to Luke 22, though,

there is an explanation: It says that the disciples had been bickering at that

very meal about who would be greatest in the kingdom. So the foot-washing in

John is explained. Jesus was giving them an example of humility and service

when they had just been competing and fighting. Luke never mentions the

foot-washing, and John never mentions the argument. Those same two passages

have a coincidence in the other direction. In Luke, Jesus scolds the disciples

for bickering and says, of himself, that though he is their master, "I am

among you as the one who serves." This is a slightly weird expression in

Luke, because he hasn't done anything especially servant-like. But if you read

about the foot-washing in John, you see that he has just dressed himself like a

servant and washed their feet. He has literally been among them as one who

serves. So the two passages fit together extremely tightly because of what each

one contains and each one leaves out. Luke explains John, and John explains

Luke.8

Despite the strong internal evidence supporting the

reliability of the New Testament, people often want corroborating evidence from

outside the Bible. This is provided by both archaeology and extra-biblical

writings. There are multiple examples of instances in which scholars doubted

the veracity of information provided in the New Testament, only to later have

it verified by archeological discoveries. For example, John 5:1-15 describes an

event in which Jesus heals a lame man who was lying near the pool of Bethesda

waiting to be placed in the water when it was stirred in hopes of being healed,

as was the local belief. Scholars doubted the existence of this pool and

thought that it was a late addition in John by someone unfamiliar with

Jerusalem. However, the pool of Bethesda was discovered in the late 19th

century and matched the Biblical description. They even found evidence of the

healing tradition associated with the pool.9

Extra-biblical writings from non-Christians also

verify key details surrounding Jesus’ life, death and resurrection. These

writings include writings from Josephus, Tacitus, Pliny the Younger, the

Babylonian Talmud, and Lucian. Since we are going to look at some of these

sources in greater detail in our next post, I won’t elaborate on them at this

time. However, if you are interested you can read the following post.

To conclude, the New Testament writings were written

by people who either directly observed the resurrection or were able to

interview those who had been eyewitnesses. Their accounts were likely written

close to the time of the actual events when other eyewitnesses would have still

been alive. Embarrassing details and unintentional coincidences provide strong

internal evidence of the truthfulness of their accounts. Certain aspects of

their testimonies are corroborated by both archeology and extra-biblical

writings. Due to the large number of manuscripts that have been preserved and

discovered, textual critics are able to ensure that the original writings have

been accurately passed down through history.

This would far exceed the criteria historians use to

evaluate the reliability of any other source, but some people will still reject

the New Testament due to perceived bias and the inclusion of miraculous events.

First, let’s deal with perceived bias. The thinking goes that since the New

Testament was written by Christians, their testimony on the resurrection cannot

be trusted. Some skeptics demand a testimony of the resurrection from someone

who was not a Christian. However, careful reflection will reveal the error in

this logic. The writers of the New Testament were only Christians because they

claimed to have seen the risen Jesus. They were not expecting the resurrection

beforehand. If an ancient non-Christian had witnessed the resurrection, they

would not have remained a non-Christian. Imagine a juror who would not believe

that a crime took place unless they heard a witness who testified to having

seen the crime, but did not believe that the crime actually took place. This

logical nonsense is similar to asking for a non-Christian writer to testify to

the resurrection.

Finally, others will reject the New Testament because

it includes miraculous accounts, such as the resurrection. The problem is that

the New Testament documents are the sources that we are using to investigate

whether a miraculous event actually occurred. The sources, which meet the

criteria of historical reliability, are rejected because they include the very

thing we are trying to explore. In other words, the question of whether the

resurrection occurred has already been answered before even beginning the

investigation due to a presupposition that miracles like the resurrection just

don’t occur. If someone rejects the New Testament and the resurrection for this

reason, I think they should just honestly admit that they have presupposed

naturalism and that they are not as open-minded towards evidence as they

probably claim to be.

Sources:

1. Ehrman, Bart. The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings, 2nd Edition, Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 47.

2.

Ehrman, Bart. Misquoting

Jesus. HarperOne, 2007, p. 10.

3.

McDowell, Josh and

Jones, Clay. “The Bibliographic Test.” Retrieved from https://www.josh.org/wp-content/uploads/Bibliographical-Test-Update-08.13.14.pdf

4.

Marrow, Jonathan.

“How Much Manuscript Evidence is there for the New Testament?” Retrieved from https://www.jonathanmorrow.org/how-much-manuscript-evidence-is-there-for-the-new-testament/

5.

Metzger, Bruce and

Ehrman, Bart. The Text of the New Testament:Its Transmission, Corruption,

and Restoration, 4th Edition. Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 126.

6.

DeWitt, Dan.

“Credo: Early Christian Creeds as Apologetics.” The O Latte. Retrieved

from https://www.theolatte.com/2019/03/credo-early-christian-creeds-as-apologetics/

7.

Shull, Margaret.

“Credible Witnesses.” Retrieved from https://www.rzim.org/read/a-slice-of-infinity/credible-witnesses

8.

McDowell, Sean.

“Unique Evidence for the New Testament: Interview with Lydia McGrew about

"Unintended Coincidences." Retrieved from https://seanmcdowell.org/blog/unique-evidence-for-the-new-testament-interview-with-lydia-mcgrew-about-unintended-coincidences-1

9.

Smith, Dean.

“Controversial Bethesda pool discovered exactly where John said it was.” Opentheword.org.

Retrieved from https://opentheword.org/2014/09/02/controversial-bethesda-pool-discovered-exactly-where-john-said-it-was/